Venetian Traveler Reveals Fascinating Details of Daily Life in 17th Century Mughal India

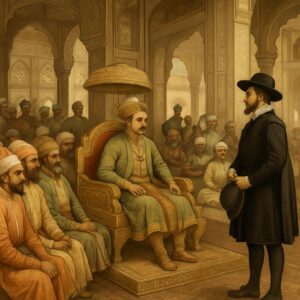

In a remarkable account that provides a rare window into the daily lives of people during the height of the Mughal Empire, Venetian traveler Niccolao Manucci has documented the vibrant social tapestry of 17th century India through the eyes of a curious European observer.

## Cultural Diversity in Dress and Appearance

Manucci, who arrived in India in 1656 at the age of 17 and spent over five decades in the subcontinent, noted distinct differences in the clothing preferences of various communities. “Most Hindus prefer white garments, creating a sea of pristine fabric in crowded marketplaces,” he observed, “while Muslims embrace a kaleidoscope of colors, their vibrant attire adding to the visual richness of urban centers.”

This observation reveals how clothing served as an immediate visual marker of religious and cultural identity in Mughal India, a practice that continues to influence traditional dress codes in the region today.

## Superior Shipbuilding Technology

In an assessment that might surprise modern readers, Manucci declared Indian shipbuilding superior to European methods of the time. “The abundance of high-quality timber and skilled craftsmanship gives Indian vessels advantages in both construction and durability,” he wrote, challenging Eurocentric assumptions about technological advancement.

Maritime historians now recognize that Indian Ocean trading vessels were indeed well-adapted to regional conditions and often incorporated innovative design elements that European shipwrights would later adopt.

## Sophisticated Traveler Infrastructure

The extensive network of sarais (roadside inns) throughout the empire particularly impressed Manucci during his journey from the port city of Surat to the imperial capital of Delhi. “These establishments offer remarkable security for travelers, with officials held personally accountable for the safety of guests and their possessions,” he noted.

This observation highlights the sophisticated infrastructure that supported commerce and communication across the vast Mughal domains, comparable to modern highway rest stops and budget hotels that facilitate contemporary travel.

## Unique Religious Practices

Manucci documented fascinating religious customs, including the Parsi practice of non-interference with accidental fires. “If a Parsi’s house catches fire by accident, they are forbidden to extinguish it, viewing the flames as a divine blessing in response to their devotion,” he wrote.

This account offers insight into the theological principles of Zoroastrianism, where fire represents divine purity and serves as a central element in worship.

## Social Etiquette and Hospitality

The offering of paan (betel leaf) as a gesture of hospitality caught Manucci’s attention as a distinctive social custom. “To decline the offer of paan would constitute a serious breach of etiquette,” he observed, noting the universal nature of this practice across social classes.

This tradition, corroborated by other historical sources including Abul Fazal and Amir Khusrau, continues in modified form in contemporary Indian hospitality customs.

## Vibrant Urban Marketplaces

Manucci’s descriptions of Delhi’s bazaars under Shah Jahan paint a picture of commercial vitality and urban sophistication. “The capital boasts vast, well-constructed marketplaces offering goods from across the known world,” he wrote, particularly noting the special “Khush Roz” or fancy bazaar established by Emperor Akbar.

This monthly market, held on the third Friday and known as Meena Bazaar, served multiple functions beyond commerce. “The emperor uses this opportunity to oversee harem activities and arrange marriages between suitable young people,” Manucci observed, revealing how commercial spaces also served social and administrative purposes.

## A Valuable Outside Perspective

Historians value Manucci’s account precisely because it comes from an outsider who noticed details that indigenous chroniclers might have taken for granted. His observations from the periphery of aristocratic circles provide a more complete picture of life in Mughal India than court histories alone.

As we continue to understand the complex social and cultural landscape of pre-colonial India, firsthand accounts like Manucci’s “Storia do Mogor” remain invaluable resources that help us see beyond political narratives to the lived experiences of people across the social spectrum.

*This historical news item is based on the observations recorded by Niccolao Manucci in his work “Storia do Mogor” (History of the Mughal), written between 1656 and 1708.*